#GrowYourLife #BuildYourBusiness

Life Area: Personal

Topic: The Role Luck Plays In Our Success

The Role Luck Plays In Our Success

I recently recorded a Talk with Tom podcast episode on the topic of the role luck plays in our success. You can listen to it [here]. For those of you who favor the written word, I offer up the fascinating findings from a number of studies I came across in my research.

The results of a recent Italian study conducted by researchers Alessando Pluchino and Alessio Biondo, dovetail with a growing number of other studies based on real-world data, which strongly suggest that luck and opportunity play an underappreciated role in determining the level of individual success. As the researchers point out, since rewards and resources are usually given to those who are already highly rewarded, this often causes a lack of opportunities for those who are most talented (i.e., have the greatest potential to actually benefit from the resources), and it doesn’t take into account the important role of luck, which can emerge spontaneously throughout the creative process.

What are the secrets of the most successful people?

Time and again things such as talent, skill, mental toughness, hard work, tenacity, optimism, growth mindset, and emotional intelligence have been cited.

Brendon Burchard from research for his recent book High Performance Habits: How Extraordinary People Become That Way identified six common habits:

Three Personal Habits including:

. Seek Clarity,

. Generate Energy, and

. Raise Necessity; and

Three Social Habits:

. Increase Productivity,

. Develop Influence, and

. Demonstrate Courage.

All these underlying assumptions influence how we distribute resources in society, from work opportunities to fame to government grants to public policy decisions. We tend to give out resources to those who have a track record of success, and tend to ignore those who have been unsuccessful, assuming that the most successful are also the most competent.

But are these assumptions correct?

Psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman wrote recently in Scientific American that he has spent his entire career studying the psychological characteristics that predict achievement and creativity. He found that a certain number of traits– including passion, perseverance, imagination, intellectual curiosity, and openness to experience– do significantly explain differences in success, he was also left dumbfounded how much of the variance is often left unexplained.

In recent years, a number of studies and books have suggested that luck and opportunity may play a far greater role than we ever realized, across a number of fields, including financial trading, business, sports, art, music, literature, and science. The dominant argument is not that luck is everything; of course talent matters. Instead, the data suggests that we miss out on a really importance piece of the success picture if we only focus on personal characteristics in attempting to understand the determinants of success. Consider some recent findings:

- About half of the differences in income across people worldwide is explained by their country of residence and by the income distribution within that country,

- Scientific impact is randomly distributed, with high productivity alone having a limited effect on the likelihood of high-impact work in a scientific career,

- The chance of becoming a CEO is influenced by your name or month of birth,

- The number of CEOs born in June and July is much smaller than the number of CEOs born in other months,

- Those with last names earlier in the alphabet are more likely to receive tenure at top departments,

- The display of middle initials increases positive evaluations of people’s intellectual capacities and achievements,

- People with easy to pronounce names are judged more positively than those with difficult-to-pronounce names,

- Females with masculine sounding names are more successful in legal careers

Are the most successful people mostly just the luckiest people in our society?

If this were even a little bit true, then this would have some significant implications for how we distribute limited resources, and for the potential for the rich and successful to actually benefit society (versus benefiting themselves by getting even more rich and successful).

In an attempt to shed light on this heavy issue, Pluchino and Biondo created a mathematical model making the first ever attempt to quantify the role of luck and talent in successful careers. In their prior work, they warned against a “naive meritocracy”, in which people actually fail to give honors and rewards to the most competent people because of their underestimation of the role of randomness among the determinants of success. To formally capture this phenomenon, they proposed a “toy mathematical model” that simulated the evolution of careers of a collective population over a work life of 40 years (from age 20-60).

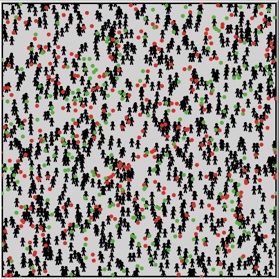

The researchers stuck a large number of hypothetical individuals (“agents”) with different degrees of “talent” into a square world and let their lives unfold over the course of their entire worklife. They defined talent as whatever set of personal characteristics allow a person to exploit opportunities (luck). Talent can include traits such as intelligence, skill, motivation, determination, creative thinking, emotional intelligence, etc. The key is that more talented people are going to be more likely to get the most ‘bang for their buck’ out of a given opportunity.

The researchers stuck a large number of hypothetical individuals (“agents”) with different degrees of “talent” into a square world and let their lives unfold over the course of their entire worklife. They defined talent as whatever set of personal characteristics allow a person to exploit opportunities (luck). Talent can include traits such as intelligence, skill, motivation, determination, creative thinking, emotional intelligence, etc. The key is that more talented people are going to be more likely to get the most ‘bang for their buck’ out of a given opportunity.

All agents began the simulation with the same level of success (10 “units”). Every 6 months, individuals were exposed to a certain number of lucky events (in green) and a certain amount of unlucky events (in red). Whenever a person encountered an unlucky event, their success was reduced in half, and whenever a person encountered a lucky event, their success doubled proportional to their talent (to reflect the real-world interaction between talent and opportunity).

What did they find?

Well, first they replicated the well known “Pareto Principle“, which predicts that a small number of people will end up achieving the success of most of the population (Richard Koch refers to it as the “80/20 principle”). In the final outcome of the 40-year simulation, while talent was normally distributed, success was not. The 20 most successful individuals held 44% of the total amount of success, while almost half of the population remained under 10 units of success (which was the initial starting condition). This is consistent with real-world data, although there is some suggestion that in the real world, wealth success is even more unevenly distributed, with just eight men owning the same wealth as the poorest half of the world.

Almost half of the population remained under 10 units of success.

Although such an unequal distribution may seem unfair, it might be justifiable if it turned out that the most successful people were indeed the most talented/competent. So what did the simulation find? On the one hand, talent wasn’t irrelevant to success. In general, those with greater talent had a higher probability of increasing their success by exploiting the possibilities offered by luck. Also, the most successful agents were mostly at least average in talent. So talent mattered.

However, talent was definitely not sufficient because the most talented individuals were rarely the most successful. In general, mediocre-but-lucky people were much more successful than more-talented-but-unlucky individuals. The most successful agents tended to be those who were only slightly above average in talent but with a lot of luck in their lives. Consider the evolution of success for the most successful person and the least successful person in one of their simulations:

However, talent was definitely not sufficient because the most talented individuals were rarely the most successful. In general, mediocre-but-lucky people were much more successful than more-talented-but-unlucky individuals. The most successful agents tended to be those who were only slightly above average in talent but with a lot of luck in their lives. Consider the evolution of success for the most successful person and the least successful person in one of their simulations:

A highly successful person had a series of very lucky events in their life, whereas the least successful person (who was even more talented than the other person) had an unbearable number of unlucky events in their life. As the authors note, “even a great talent becomes useless against the fury of misfortune.”

The most talented individuals were rarely the most successful.

So what can be done?

Talent loss is obviously unfortunate, to both the individual and to society. So what can be done so that those most capable of capitalizing on their opportunities are given the opportunities they most need to thrive?

A study by Carleton Institute researchers Jean-Michal Fortin and David Currie found that merit strategies used to assign honors, funds, or rewards are often based on the past success of the person. Selecting individuals in this way creates a state of affairs in which the rich get richer and the poor get poorer (often referred to as the “Matthew effect“). But is this the most effective strategy for maximizing potential? Which is a more effective funding strategy for maximizing impact to the world: giving large grants to a few previously successful applicants, or a number of smaller grants to many average-successful people? This is a fundamental question about distribution of resources, which needs to be informed by actual data.

Fortin and Currie found that the least effective funding strategies are those that give a certain percentage of the funding to only the already most successful individuals. The “mixed” strategies that combine giving a certain percentage to the most successful people and equally distributing the rest is a bit more effective, and distributing funds at random is even more efficient. This last finding is intriguing because it is consistent with other research suggesting that in complex social and economic contexts where chance is likely to play a role, strategies that incorporate randomness can perform better than strategies based on the “naively meritocratic” approach.

The best funding strategy of them all was one where an equal number of funding was distributed to everyone.

With that said, the best funding strategy of them all was one where an equal number of funding was distributed to everyone. Distributing funds at a rate of 1 unit every five years resulted in 60% of the most talented individuals having a greater than average level of success, and distributing funds at a rate of 5 units every five years resulted in 100% of the most talented individuals having an impact! This suggests that if a funding agency or government has more money available to distribute, they’d be wise to use that extra money to distribute money to everyone, rather than to only a select few. The researchers conclude,

“If the goal is to reward the most talented person (thus increasing their final level of success), it is much more convenient to distribute periodically (even small) equal amounts of capital to all individuals rather than to give a greater capital only to a small percentage of them, selected through their level of success – already reached – at the moment of the distribution.”

Conclusion

The results of these studies strongly suggest that luck and opportunity play an underappreciated role in determining the final level of individual success. Success may truly lie at the intersection of preparation meeting opportunity, however, that is not the entire story. As the researchers point out, since rewards and resources are usually given to those who are already highly rewarded, this often causes a lack of opportunities for those who are most talented (i.e., have the greatest potential to actually benefit from the resources), and it doesn’t take into account the important role of luck, which can emerge spontaneously throughout the creative process. The researchers argue that the following factors are all important in giving people more chances of success: a stimulating environment rich in opportunities, a good education, intensive training, and an efficient strategy for the distribution of funds and resources. They argue that at the macro-level of analysis, any policy that can influence these factors will result in greater collective progress and innovation for society (not to mention immense self-actualization of any particular individual).

Please share this post with your family and friends.

My mission is to inspire people and organizations to live their highest vision.

I am a Success Strategist and Master Coach. I provide transformational coaching and training for individuals and organizations to help you Grow Your Life and Build Your Business by getting clear and focused on what you want, why you want it, and how to create it. Learn more about me at SuccessSeriesLLC.com.

There is no better endorsement than that of a friend, so if you like what you’re reading or are using my many FREE resources, tell a friend to join the Tom Hart Success Series Community, to receive email notifications of new blog posts and Talk with Tom podcast episodes, learn of upcoming events, and other news, by visiting my website and clicking on the offer to receive my FREE monthly resource by leaving their email address OR forward this to them and have them simply click here (we respect your privacy and do not tolerate spam and will never sell, rent, lease or give away your information to any third party).